- Education

-

Research

Current research

Talent

-

Collaboration

Businesses

Government agencies and institutions

Alumni

-

About AU

Organisation

Job at AU

Can we learn from universities abroad who try to break down the 'boys’ club culture' that prevents equality from penetrating the professors' offices? Meet two female Health researchers from DANWISE, who call for active support and better data on the conditions we want to change.

2020.10.29 |

Some universities work with a kind of ‘mentoring’, where an active mentor – also called a sponsor – has entrusted responsibility for introducing both male and female talents to the powerful prestigious contacts, says Christine Parsons (left) and Ida Vogel - who hereby passes on a concrete suggestion. Photo: Jann Thiele Zeiss, AU-Health.

The road to academic credit, research collaborations and ultimately professorships is paved with powerful prestigious contacts - also called vertical networks.

But informal coffee meetings with an opportunity to greet an important research leader or meet university managers are often reserved for male researchers. These seemingly small meetings and opportunities accumulate, and leave some women with a sense of the university as an impenetrable ‘boys’ club’, say two female Health researchers, associate professor Christine Parsons and clinical professor, DrMSc. Ida Vogel, both from the Department of Clinical Medicine.

Parsons and Vogel are vice chairwoman and co-vice chairwoman of The Danish Society for Women in Science (DANWISE), an organization which works for a better gender balance and increased awareness of barriers to diversity.

According to Vogel and Parsons, recent evidence shows that male researchers are more likely to work with other male researchers, and that might explain why men invite men into their informal vertical networks:

“It is well-documented in research and partly locally described that male researchers introduce peers, including newly-hired talents, to people in higher positions who directly or indirectly open up opportunities and resources, Ida Vogel says. Christine Parsons adds:

”In the UK, it has been shown that new female group leaders end up with statistically less money and less laboratory space than their male peers. It speaks to the need to understand what happens in Denmark,” Christine Parsons says with a reference to the study of research culture in the UK, published in eLife.

Parsons points out that there are even gender differences in who researchers cite, with women being under-cited compared to men in various disciplines. Both citations and being part of networks are crucial for researcher visibility which, in turn, impacts who is invited to give a talk, be a grant co-applicant and who receives awards.

All in all, it is no wonder that Parsons and Vogel meet frustrated female researchers in DANWISE, some from Health and some from Aarhus University in general. DANWISE provides a space for sharing stories that are not easy to tell elsewhere because no one wants to be the demanding or ‘troublesome’ employee.

“An example is a Health researcher from abroad who has a stellar publication record, but who struggles to get her own office space and resources initially promised,” says Ida Vogel – pointing out that few women would demand working conditions that match their male colleagues.

“For some female researchers, this also would be social suicide. But the risk is that female talents, who we have been lucky to educate or draw to Aarhus, leave us in favor of universities that treat female researchers more favourably. For example, some universities work with a kind of ‘mentoring’, where an active mentor – also called a sponsor – has entrusted responsibility for introducing both male and female talents to the powerful prestigious contacts,” says Ida Vogel - who hereby passes on a concrete suggestion in an area where Parsons has a personal experience:

“Having such a sponsor – a professor who brought me along to grant application meetings, who put me in contact with his network – and continues to do so – has been incredibly helpful for me”, says Parsons.

Christine Parsons also points out that several universities abroad put the spotlight on female role models. A tangible example is found at one of the most acclaimed universities in the UK, King’s College London.

“At King’s, the main building of their world-renowned Institute of Psychiatry presents an impressive exhibition of the portraits of their leading female professors. It is a clear celebration of their female academics – a signal that the university is proud of all the talented women who have made King's the place it is today,” says Christine Parsons, who left another prestigious workplace, Oxford University, to live and work with us.

“I still remember my first months in Aarhus, browsing around the faculty's websites and checking out the new and old university buildings - looked at the works of art on the walls, getting a grip of Aarhus University. I remember thinking ‘gosh, where are the women?’ The absence of female professors, and females in senior management positions is striking” says Christine Parsons.

This brings Ida Vogel to an important point from her position as a female professor at a department where only 19 percent of the clinical professors are female: You have to count and register what you say you want to change, because how else should you could check if it is going the right way?

“Nationally, only one in four professors is a woman, but how does our faculty appear when you calculate by gender? And the departments? If you have an area of focus, you need to create your own – publicly available – data, which you evaluate on a regular basis. I therefore hope that Health are going to present the exact numbers,” says Ida Vogel.

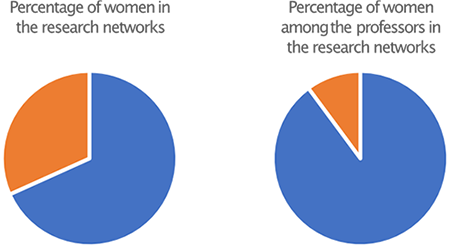

DANWISE recently counted the number of men and women in the steering groups for Health's five research network as well as the number of male and female professors. And as shown in the visualization below, there is room for improvement:

In the research networks’ steering groups, every third member is a woman (orange), while the rest of the members are men (blue). But women comprise only 10% of the total number of professors in the groups.

"When you check out Health in numbers, it turns out that the faculty had 210 professors last year, which is 11 more than the 199 professors registered in 2015. But did we hire more women, and is it progressing at a pace that is satisfactory?” Ida Vogel asks.

In any case, it is difficult to be satisfied when it comes to prizes for women in academia. According to Nature Comment, there is a consensus that women who win prizes get less money and prestige than male colleagues.

“Take for example the recent 2020 Lundbeck Talent prizes for health research, where all 4 went to males,” Parsons says. “Three of these prizes went to male PhD students - a career stage where we have a more equal representation of men and women. When DANWISE inquired about the outcomes, a Lundbeck representative explained that most of the nominations for the talent prizes were for male candidates,” she says.

According to Christine Parsons and Ida Vogel this speaks to the importance of networks – having a sponsor who will put you forward for a prize. They also both draw attention to the stereotyped ideas of female PhD students as being ‘hardworking’, but male students as having the potential ‘genius’ ideas’.

“Those of us who were fans of the 1990’s science fiction “The X-files” will be familiar with Mulder and Scully, the FBI special agents. Scully is the hard-working, conscientious female agent, who often lays the ground-work for Mulder to come along with his genius breakthroughs," Parsons says.

“While this is only a TV show, it underlines the gender-stereotypes we have all grown up with. We should be reminded that we have a responsibility to consider who we are nominating for these prizes, and whether there are biases in who we put forward”.

Both Health and Aarhus University focus on improving gender equality and diversity in the academic environments.

Associate Professor Christine Parsons

Aarhus University, Health, Department of Clinical Medicine

Interacting Minds Centre

DANWISE

E-mail: christine.parsons@cas.au.dk

Mobile: 29 88 87 75

Professor DrMSc Ida Vogel

Aarhus University, Health, Department of Clinical Medicine

Aarhus University Hospital

DANWISE

E-mail: iv@clin.au.dk

Mobile: 31 52 31 56